Walking Around Money

by Paul Miles

Mrs. Coulston told the man from Claude Wickard's Department of Agriculture that I could run a projector. He came by our house and asked after me--I don't think anyone had ever done that before. Anyway, my mother came to our room and told me a Negro gentlemen wanted me, which was her way of saying he looked distinguished because we always called ourselves colored. He told me what he needed--it would be Sunday afternoon and all I would have to do is thread the film he'd give me and run the projector after he gave a little talk. For that, he would pay me fifty cents now and a dollar-fifty after, which was pretty good walking around money.

It was Friday evening when he'd come. He had business in, I think he said Bryan and Rockdale. And like I said, four bits was nice to have, but it was too late to go and do anything that day.

When I woke up on Saturday, my father and my brother Elijah had already gone out to the dry cleaners my father owned. The rest of our family sat around the red table we had then and ate breakfast, which was scrambled eggs, cheese grits, bacon, with some toast to sop it up with. My sister Jewel was reading from a letter we had got from our cousin Murray, who was a truck driver in the Army somewhere in Europe. He had been in a great battle and tried to tell us whereabouts, but there were black strikethroughs on the letter in those parts.

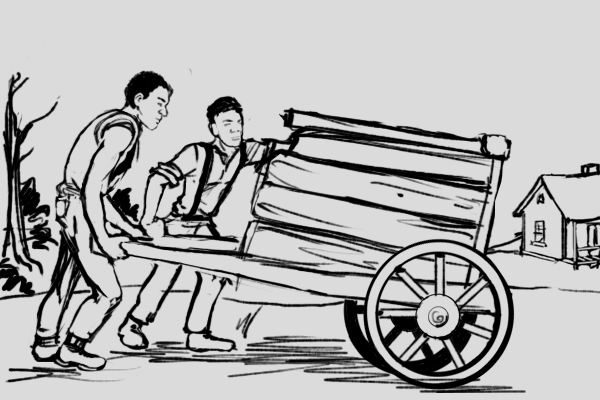

After we finished eating, I had a chore to do with my brother Ed. We had to go and gather some wood for the stove; the logs were kept in a white painted shack on the other side of our property. Between the house and the shack was a field, left grey and empty in winter. We took the wheelbarrow, bouncing across the field's empty rows to the shack--opened the door, which I hated going in there because one time at night I'd opened it and a bat flew right by my face. Anyway, there was nothing like that this time and we piled some old logs into the barrow and brought them back to the house. Ed pushed and I held my hand over the top to keep them from jostling out. Thinking back on the letter, I asked Ed if he thought any of the Germans they had captured would end out back here. I told him I thought it was funny that Murray, who had grown up in the house across the street from us, was over the sea and that some of the men he fought had switched places with him. Ed said he figured not, since the camp seemed pretty full, but allowed the idea was humorous.

When we piled the logs against the side of the house, my chores were done for the day. As I think I said, it was winter, the coldest I would ever be until some eight years later when I stood bayonet to bayonet with a Sumatran orangutan screeching Mandarin from its voicebox less than two miles south of the Yalu, which obviously is another story. We didn't have school and we didn't have any work to do in the fields, which we would have had if it had been spring or summer.

I had told Ed about the money I'd got and he'd given me an idea of how to spend it and make even more money, which he was always good at. We borrowed the wheelbarrow and headed towards the main part of town. Hearne, Texas is separated in half by railroad tracks and the colored people live on the east side, whites to the west--though the Negro cemetery is on the white side of town, which I've never understood. Anyway, Ed and I came to Main Street, to the Piggly Wiggly, or was it Schwegmann's then, I don't remember--anyway, we had one fancy sort of grocery store in the center of town, kitty corner from the city hall. We started to go in, but Mr. Crossley, the store manager who I remember had a face kind of like a hog, said let me see your money, and I held it out for him. Then he said only one of you can come in, and I turned to Ed, since this was his idea, but he shrugged and muttered, 'I don't give a shit,' which is the way he's always talked. So I went in.

I bought a bunch of stuff like bread and chocolate and some bologna meats and then me and Ed put it all in the wheelbarrow and headed out towards the German prisoner of war camp. Now it was about noon--I could tell because in Hearne they always fired off the air raid siren to let everybody know that it was suppertime. The POW camp was back across the colored part of town and just outside the city limits. After the war, they made the camp into the colored elementary school. Two of my sisters went there. After we heard the siren, we figured we just as well could stop off at home to eat. Ed figured the Nazis weren't going anywhere. Mama wasn't there so we made some sandwiches and had sweet tea. We sat outside for a little while, then we got back to the wheelbarrow and rolled it the rest of the way to the camp. Like always, we could smell the camp before we saw it. If the wind blew wrong, the stench would cover the whole colored part of town. With hindsight, it would be easy to say that it was the smell of a slaughterhouse, but I really don't remember it that way. To me it was more like the sharp haze from a soldering iron. And I also remember the white folks always saying that they couldn't smell a thing.

Camp Hearne, which is what they called it, was a big square carved out of the thick Brazos woods. The ground was red clay not black like the rest of the bottom land nearer the river. They'd built some of the buildings out of the trees they'd cut down but the rest were standard Army tin. The fence was made of barbed wire, which reached high over our heads. We'd been inside the camp before because my father's dry cleaners had some of the business of laundering uniforms for both the Germans and the American guards. Ed said we couldn't just walk in the front so we rolled the barrow off the road and through the trees towards the back of the camp. When they'd built the place, they'd cut down enough trees so there was a gap between the camp and the woods, except in the back where I guess the soldiers had gotten lazy because the tree line was almost up against the fence. We could see the Nazis walking around--to be honest, they looked the same as any other white folks, maybe less kept up because some of them had stopped shaving. And we could see the guards walking along inside the fence, green helmets with a red 'A' on them. Ed and I stayed in the trees so they couldn't see us. He told me to watch--he'd been to the camp more than me because he was older--watch and the guards'll turn around. And they did.

We came out of the trees, rolled the wheelbarrow right up to the fence. Ed whistled to some Nazis he saw kicking a ball around and motioned for them to come on over. They did and we showed them what we had. What Ed knew was that some of the Germans had money--their families back home sent it to them or they got paid by the US government for doing work. They couldn't hardly speak English and we couldn't take in their language, but we held up fingers and pretty much understood one other. They would shove money through the gate and we tossed the food over the fence. It was fine till we heard a yell and saw one of the guards running towards us, hand on his pistol holster.

'Goddamit,' Ed said as he stuffed the money into his pocket. The Nazis gathered their food and ran away laughing as this roughneck white boy comes huffing up and grabbed us both by the neck: 'What'r you two niggers doing?'

Which seemed kind of obvious really, but anyway. The guard marched us up to the gate and I guess he would have called the town police or something but there was Dad's red Ford pickup truck. He was at the camp on a laundry run and now we saw him coming out of the barracks with my oldest brother Elijah. Ed muttered under his breath when he realized Father had seen us.

He came up quick and the guard asked. 'Are these yours?'

He said yes and pushed us towards the truck, with his eyes kind of darting back and forth to see if anyone else was watching. He and Elijah tossed the laundry sacks into the back of the pickup, Ed hopped into the back and reached back to help me up into the truck bed.

One of the reasons I knew I couldn't spend my whole life in a small town is that I never figured out how to ride natural in the back of a pickup truck. We were in there with about six or seven big white canvas sacks and I sat in the bed because I could always imagine me falling out if we hit a bump. Ed stood up and leaned against the tailgate.

We came up to the dry cleaners--a tiny red brick building just near the tracks but still on the colored side of town. We hopped down from the truck and carried the sacks into the store. It might have been freezing outside but it was always like a furnace in the cleaners. In summer, you could almost faint if you didn't take regular breaks. Even now the heat hit you the moment you opened the door. And those sacks were heavy; Ed and Elijah could hoist two at a time, so could my father. I could barely carry one and by carry I mean practically drag the sack behind the green countertop and into the back.My Uncle Garland, just back from the Pacific--he limped but never complained about it, said he had the luckiest wound ever--was working with my father at that time and he started to separate out the sacks, Germans on one side, the guards on the other. As the Germans' clothes tumbled out, he stepped back and covered his nose, gingerly picked up one of the shirts. It was stiff with caked blood. Uncle Garland said 'Look at this--every damn time.'

I leaned in closer to see as his thumb rubbed through the blood and caught against what looked something like dark pink flesh, like a fish after you scale it. He nicked the piece off and it dropped to the floor. He said, 'Skin ain't supposed to look like this. One night when we were off Rebaul, a ship on station with us had its boiler explode--it only takes a little spark--and a day later, after it'd finally burned out, me and some others crossed over and went on board to see if anyone was alive. One poor man did live, looked as though he'd been turned inside out.'

About the Author

About the Artist

|