|

page 2 of 8

|

|

|

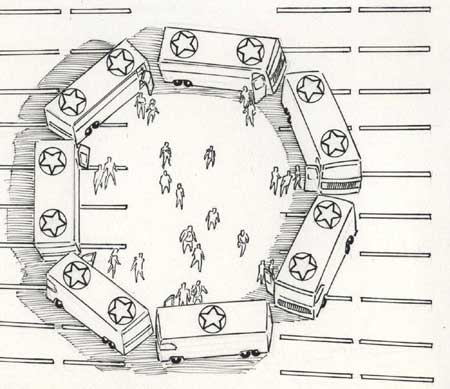

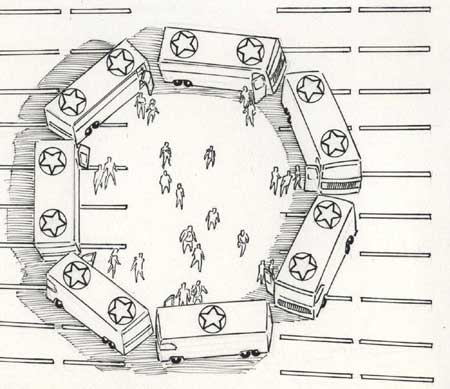

He came on schedule, even slightly early. There was only a small crowd, as the rock star's organization had sought confidentiality. A train of seven monstrous busses pulled into the hotel's lot, their whale-like sides gleaming with brushed aluminum. They bore Massachusetts license plates. I walked out on to the tarmac and began photographing. All seven busses carried the rock star's favored insignia, the thirteen-starred blue field of the early American flag. The busses pulled up with military precision, forming a wagon-train fortress across a large section of the weedy, broken tarmac. Folding doors hissed open and a swarm of road crew piled out into the circle of busses. Men and women alike wore baggy fatigues, covered with buttoned pockets and block-shaped streaks of urban camouflage: brick red, asphalt black, and concrete gray. Dark-blue shoulder-patches showed the thirteen-starred circle. Working efficiently, without haste, they erected large satellite dishes on the roofs of two busses. The busses were soon linked together in formation, shaped barriers of woven wire securing the gaps between each nose and tail. The machines seemed to sit breathing, with the stoked-up, leviathan air of steam locomotives. A dozen identically dressed crewmen broke from the busses and departed in a group for the hotel. Within their midst, shielded by their bodies, was the rock star, Tom Boston. The broken outlines of their camouflaged fatigues made them seem to blur into a single mass, like a herd of moving zebras. I followed them; they vanished quickly within the hotel. One crew woman tarried outside. I approached her. She had been hauling a bulky piece of metal luggage on trolley wheels. It was a newspaper vending machine. She set it beside three other machines at the hotel's entrance. It was the Boston organization's propaganda paper, Poor Richard's. I drew near. "Ah, the latest issue," I said. "May I have one?" "It will cost five dollars," she said in painstaking English. To my surprise, I recognized her as Boston's wife. "Valya Plisetskaya," I said with pleasure, and handed her a five-dollar nickel. "My name is Sayyid; my American friends call me Charlie." She looked about her. A small crowd already gathered at the busses, kept at a distance by the Boston crew. Others clustered under the hotel's green-and-white awning. "Who are you with?" she said. "Al-Ahram, of Cairo. An Arabic newspaper." "You're not a political?" she said. I shook my head in amusement at this typical show of Soviet paranoia. "Here's my press card." I showed her the tangle of Arabic. "I am here to cover Tom Boston. The Boston phenomenon." She squinted. "Tom is big in Cairo these days? Muslims, yes? Down on rock and roll." "We're not all ayatollahs," I said, smiling up at her. She was very tall. "Many still listen to Western pop music; they ignore the advice of their betters. They used to rock all night in Leningrad. Despite the Party. Isn't that so?" "You know about us Russians, do you, Charlie?" She handed me my paper, watching me with cool suspicion. "No, I can't keep up," I said. "Like Lebanon in the old days. Too many factions." I followed her through the swinging glass doors of the hotel. Valentina Plisetskaya was a broad-cheeked Slav with glacial blue eyes and hair the color of corn tassels. She was a childless woman in her thirties, starved as thin as a girl. She played saxophone in Boston's band. She was a native of Moscow, but had survived its destruction. She had been on tour with her jazz band when the Afghan Martyrs' Front detonated their nuclear bomb. I tagged after her. I was interested in the view of another foreigner. "What do you think of the Americans these days?" I asked her. We waited beside the elevator. "Are you recording?" she said. "No! I'm a print journalist. I know you don't like tapes," I said. "We like tapes fine," she said, staring down at me. "As long as they are ours." The elevator was sluggish. "You want to know what I think, Charlie? I think Americans are fucked. Not as bad as Soviets, but fucked anyway. What do you think?" "Oh," I said. "American gloom-and-doom is an old story. At Al-Ahram, we are more interested in the signs of American resurgence. That's the big angle, now. That's why I'm here." She looked at me with remote sarcasm. "Aren't you a little afraid they will beat the shit out of you? They're not happy, the Americans. Not sweet and easy-going like before." I wanted to ask her how sweet the CIA had been when their bomb killed half the Iranian government in 1981. Instead, I shrugged. "There's no substitute for a man on the ground. That's what my editors say." The elevator shunted open. "May I come up with you?" "I won't stop you." We stepped in. "But they won't let you in to see Tom." "They will if you ask them to, Mrs. Boston." "I'm Plisetskaya," she said, fluffing her yellow hair. "See? No veil." It was the old story of the so-called "liberated" Western woman. They call the simple, modest clothing of Islam "bondage" -- while they spend countless hours, and millions of dollars, painting themselves. They grow their nails like talons, cram their feet into high heels, strap their breasts and hips into spandex. All for the sake of male lust. It baffles the imagination. Naturally I told her nothing of this, but only smiled. "I'm afraid I will be a pest," I said. "I have a room in this hotel. Some time I will see your husband. I must, my editors demand it." The doors opened. We stepped into the hall of the fourteenth floor. Boston's entourage had taken over the entire floor. Men in fatigues and sunglasses guarded the hallway; one of them had a trained dog. "Your paper is big, is it?" the woman said. "Biggest in Cairo, millions of readers," I said. "We still read, in the Caliphate." "State-controlled television," she muttered. "Worse than corporations?" I asked. "I saw what CBS said about Tom Boston." She hesitated, and I continued to prod. "A 'Luddite fanatic', am I right? A 'rock demagogue'." "Give me your room number." I did this. "I'll call," she said, striding away down the corridor. I almost expected the guards to salute her as she passed so regally, but they made no move, their eyes invisible behind the glasses. They looked old and rather tired, but with the alert relaxation of professionals. They had the look of former Secret Service bodyguards. The city-colored fatigues were baggy enough to hide almost any amount of weaponry. |

|

| Back | |