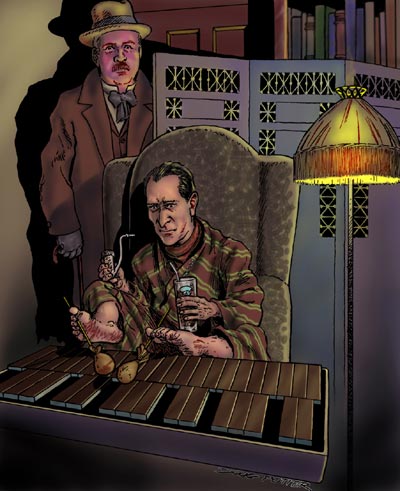

Written with the sincerest apologies to S. Holmes and none whatsoever to his ten thousand shadows. Our story opens when The Poor Stooge returns from an afternoon's walk to find The Great Detective wrapped in his old green dressing gown. (Which he himself made from a horse blanket, and which has remained uncleaned since.)* His right hand grips a Coke in which floats a Benzedrine inhaler. He is playing the xylophone with his toes. These symptoms, as The Poor Stooge knows from long experience, mean that The Great Detective has a case which is baffling police throughout the world, and has the newspapers of a continent reduced to wild conjectures. All his cases fall into this category, of course, except for those which are so secret and of such vital importance to the national welfare that they are brought to him by the president or king of a foreign power, or the prime minister himself. On such occasions he is found wearing his horse disguise, and impatiently waiting for The Poor Stooge to act as his rear guard, the one thing that gentleman does to perfection. After several minutes of rapt xylophone playing The Great Detective looks up at The Poor Stooge, who has been waiting with dog-like devotion for the great man's words. "On your walk," intones The Great Detective, "you paused to pat the head of a small boy who was eating a lime popsycle." "Astounding!" Gasps The Poor Stooge, "How do--" "I noted the marks on your hand, where he bit you as small boys always do when you pat their heads. Not that I blame them." "But the--" "The popsycle was an easy inference. Your right arm is covered from wrist to elbow with a sticky green smear which could only come from such a confection. "Furthermore, you aided some such moppet in getting a drink from the park fountain." "Ho--" says The Poor Stooge, who by this time is reduced to gibbering incoherence despite the fact that this has happened to him in all the other stories by the same author. "He squirted you, and you are still dripping wet. Also, you went to the Swineherds Midtown Bank and withdrew an amount less than six and a half crowns, five shillings, tuppence." The Poor Stooge stands mute. He is too numb for further amazement. The reader is simply numb. "I deduced this from the fact that you stuck the bank's pen in your pocket and your shirt-front is saturated with the vile black ink peculiar to the Swineherds. Had the amount exceeded that sum you would have been more thoroughly disturbed and would have put the pen in your mouth so that your lips, rather than your haberdashery, would have been black. But enough of this idle chitchat, I have just received a missive concerning a case which promises to be of some interest." The Great Detective's statement is followed instantly by the entry of an old apple-woman. "Greetings, Sir Humphrey Blassington-Smyth of Little Slopshire on the Gimlet," drawls The Great Detective. "Gad, sir!" exclaims Sir Humphrey. (For, as the reader may have guessed, it was really he.) "I believed my disguise to be impenetrable. After I was expelled from the grounds of Blassington hall by my own butler and bitten by my own dog, Black Herbert of Slopshire XVII, whose ancestors served with mine at the battle of Hastings, I would never have believed that a perfect stranger would recognize me. How did you manage it?" "Your disguise, Sir Humphrey, is that of a brilliant amateur, and suffers from the common defect of its kind. While painstaking in some respects -- I did not fail to notice the genuine lice bites on your wrist--" "It was nothing, I simply put my arm around the cook for a few minutes," mumbles the peer modestly. "As I was saying, like most amateurs you overlooked one major point. As you entered I perceived that the apples in your basket were not actually apples, but cannon balls, door knobs, and a few darning eggs, painted scarlet. Once I was assured of your fraudulency, identification was not difficult. Your picture, you may recall, appeared on the third page of The Times a fortnight ago come Martinsmas in connection with a charity foxhunt. By the way, what was the result of that hunt?" "Little blighter got away." "My question, sir, was in reference to the proceeds of the hunt. Did the Hurbut Gelding Fund For the Prosecution of Immorality fatten its purse as expected?" "Dash it all! I thought it was for The Unwed Mothers Home." "I believe not. But what was this matter on which you wished to consult me?" "As a man with your knowledge of London affairs is no doubt aware, my family, while one of the oldest in England, was up to a few years ago, totally impoverished." "This was due to the attempts of your grandfather, a felineophobiac, to construct a clockwork mouse which would rid England of cats, was it not?" "Yes. The family fortune could have stood it were it not for his passion for jeweled bearings; those bearings beat us. Are you also familiar with the way in which those fortunes he spent have been regained?" "No." (The Great Detective was always inclined to be a little rude when he was unable to answer a question.) "I recall it as though it were yesterday," says Blassington-Smyth. "The family was gathered about the fire in old Castle Blassington, the last habitable building left to us. Upon the fire we bad just thrown the last piece of good furniture left in the castle, a Louis XIV commode. Then came a knock at the door." "Who was it?" gasps The Poor Stooge, grabbing The Great Detective's hand for assurance.

|

|