|

Page 1 of 7

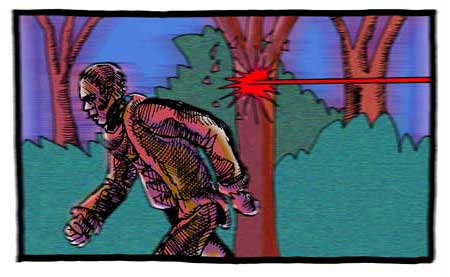

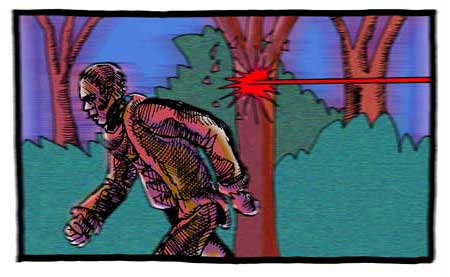

Sri Mani's bullet clipped a twig near my head, punched a perfectly symmetrical hole in the broad red leaf of a plant that closely resembled a poinsettia, and hissed off through the forest. A couple seconds after its passage, the dull thunder of the musket reached me, shattering my reverie. For no apparent reason, I'd been thinking about Kyle. Remembering the way he used to hold our hands and swing between Connie and me while walking through the shopping mall. I was trying to remember why it used to aggravate me so. But something about that fifty caliber musket ball breezing past my ear reminded me that Sri Mani and Nanda, his assistant, were no longer hunting honey. They were hunting me. It hardly seemed important to wonder why I hadn't appreciated Kyle when he was alive, not with the echo of that shot whispering in Nanda's raspy voice, "You are next, Bahktur. Pholo will make forest of you." How long to reload? Another ball. Powder. Something for a patch (I pictured Nanda using that wicked Gurkha knife of his - the one I'd seen him use to dispatch a full grown boar - to cut small rags from the hem of his woolen wrap). Then the rod from the underside of the barrel packing it all down. Replace the percussion cap - how many of those did Sri Mani have? Surely they weren't cheap. Surely he couldn't afford many, not when he had to go all the way to Kathmandu for them. And finally, I could picture him raising the musket back to his shoulder, lining up his eye with the sights, lining up one dumb fucking American who'd come to Nepal because he believed it was the last place on Earth for the truth to ever catch up with him. One dumb fucking American - a.k.a. me. I ducked into the nearest brush, wincing as the course branches tore at my face, and scrambled away, keeping low, limping. Waiting for the bark of the rifle again. Knowing that by the time I actually heard it, it would be too late and the lead ball might already be buried in my back. Ten feet and the ground pitched out from under me. I slid, bruising shins and tearing my palms on jagged rock, coming up short against a storm-ravaged stump. It wasn't much of a fall - leastwise not when compared with Nanda's cutting my safety line this morning. The stump tore my shirt and gouged a furrow in my side, further aggravating my bruised ribs, but the shot I'd been waiting for didn't come. Looking back, I saw why. For the time being, the edge of this shallow ravine hid the two honey hunters from sight. For at least as long as it took them to rappel down the cliff face and climb back up through the valley and over this verdant peak, I was safe. I had some time to think. Some time to recall how I'd come here. And, more importantly, to figure out how I was going to get out alive.# The village of Bahadur was hidden so deep in the Himalayas as to discourage any contact with the outside world. Tourists didn't visit. Pilgrims and holy men en route to the monasteries to the northwest found easier routes along the Brahmaputra River. The Zangbo and mainland China lay over the peaks, impassable. Kathmandu was four days away through dense forest. Mount Everest was more accessible by air. There was, in short, no reason for anyone to visit Bahadur. Only those who'd become truly lost ever found themselves there. Lost is exactly what I was. I'd been lost for over three years when I came to Bahadur. I was still mourning the death of my son. Full of self-loathing. Still reeling from the bitter hatred I'd last seen in the eyes of the woman I loved. When she told me to leave, I don't think Connie realized just how far I'd go. Or perhaps she did; she'd been married to me long enough to know my extremes. Perhaps she simply didn't care. I first found myself in Sri Lanka at the home of another writer I knew from my days with National Geographic. When I wore out my welcome there (even the best of friends tend to tolerate heavy drinking and self-pity for only so long), I crossed the Bay of Bengal and lost myself in India. I drifted up the coast for two years, accepting work when it was offered and I could keep my senses about me long enough to collect a paycheck. When I couldn't find work, I stole what I needed to survive. I was a wreck, clad in filthy rags no better than the lungis wrapped about the waists of beggars (with whom I'd spent a fair share of my time). I'd gone from pickling myself on my friend's expensive liquor to the cheap and readily available apang, a fermented grain concoction that tasted like goat's piss and took several gallons to put me into my usual stupor. By the time I'd pass out from drinking the stuff, I would have crammed so much of it into my bladder that I'd wake up floating in a puddle of my own urine. Worse, I'd generally roll over and go back to sleep, beyond even caring.But it wasn't until I reached Calcutta that I hit rock bottom. I lost thirteen months in Calcutta, doing what and with whom, I still can't recall. Drugs replaced the alcohol. There were injections. There were pipes. There were exotics that stank of cobra venom and opium and God knows what else. There were months that I never saw the sun. Weeks that the only waste leaving my body came up through my mouth and nose. It wasn't until I woke one morning in a feces-clogged gutter behind a brothel, a toothless old man in fine yellow robes bending over me with several rupees in his hand saying, "Baksheesh, baksheesh," that I began my fight up from the bottom. I didn't want to know what I'd done to earn that tip. I didn't want to know why I was naked in an alley in Calcutta, or why two men tried to drag me back into the brothel, or why I was down to 140 pounds, or why my hands shook so bad that I couldn't hang on to the coins, or . . . I found a monastery, hoping to seek sanctuary among the monks there. They beat me with cane poles and chased me out into the streets. Children took up the assault from there, harrying me northward out of the city, pelting me with stones, kicking me in the ass as I scrambled about on all fours. North of Calcutta, somewhere on a dirt road rutted by busses and littered with llama dung, I curled up to die beside the steaming carcass of a yak. There ensued several days of heat and flies, starvation and sunburn and pestilence. I was delirious with fever. Wracked by substance withdrawal. Travelers rolled me from the road and into a ditch. Insects laid their eggs in my eyes and beneath my skin. The mud of the ditch sucked up around me, while rodents nibbled at my extremities and the dogs who came to fight over the yak waited for their turn at me. But death did not find me. Eventually I found my feet and continued northward. I stole some rags. I begged for food. I ate raw corn from a farmer's field and eggs from his hen house. By the time I reached Jamshedpur, I was beginning to resemble a human being again. I had bathed in a pond and shaved with broken glass. I found work clearing brush from a construction site. A Frenchman named Montbéliard gave me a hundred rupees and a ride to Patna near the Ganges. With Montbéliard's money, I bought used, but sturdy clothing from a street merchant. In the Ganges River, I washed away the last of Baxter Lewis. With the dirt and blood and dead skin that flowed away from me down the river went the truth of who and what I'd been, the sins that I'd committed, the man that I had come to hate. I wasn't sad to see any of it go. I wasn't interested in the truth any more than I was interested in returning to any semblance of a normal life in the States. But neither was I any longer interested in death. I'd taken my best shot at killing myself and failed miserably. It was time for something other than self-destruction. I continued north, through the town of Varanasi and up into the foothills of the Himalayas. The roads grew steeper, then disappeared altogether. Goat trails drew me ever higher, into thin air, moist clouds, and thick, damp vegetation. Where the forests hadn't been cleared and sold off as lumber, the overpowering essence of life that dripped like honey from every Nepalese leaf and limb took root in the poisoned pores of my flesh and flowered, rejuvenating my soul. I was alive again. The higher I went, the less of civilization I saw, and the more alive I became. When I finally stumbled on Bahadur, it was Nanda who spotted me first. "Drokpa?" he asked in that cancer-clogged rasp of his. "Yes," I whispered. I am indeed a nomad. A wanderer. An exile of life. There is no past. There is no future. There is no truth. There's only here and now. Here, at the end of the Earth. "Bahktur," he called me, unable to pronounce my name. I nodded. Yes, that's right. Baxter Lewis is dead. Only Bahktur remains. If only it had been that easy... |

|